Are Our Museums (and Google) Promoting Cultural Exchange, or Colonialism?

Image Source: Google Arts & Culture

As this year continues to be defined by unexpected surprises, I can still recall my initial one. I had made plans to visit the Museum of Modern Art in New York in January, but they had to be cancelled at the last minute as a result of anticipated snowstorms that, as it turned out, didn’t actually occur.

Rescheduling became impossible after the coronavirus pandemic shut down the country. Now, MoMA is set to reopen after months of closure today, and Philadelphia’s cultural institutions are set to return to operation soon next month.

In a time of isolation, the cancellation of that trip has stuck in my craw. As global leaders have increasingly devalued cultural exchange and understanding, museums and art galleries are important in advancing understanding between lonely and scared Americans and people across not only space but time also.

During the last museum experience I had ahead of the pandemic, I travelled to Doylestown accompanied by Yoona, a South Korean contributor to this magazine, and despite our totally different backgrounds, both of us could appreciate the oddball historical artifacts displayed in the Michner Museum. I have more memories of that day than two entire months of total lockdown (according to science, this is only logical).

As spring started to pass and the pandemic saw us cooped up indoors, I discovered Google Arts and Culture in the midst of browsing absentmindedly, a site compiling the intellectual heritage of museums and galleries globally, and promptly lost any time that night I might have otherwise used to be productive.

Google Arts and Culture, like Zoom, had a pre-pandemic life, but since lockdowns led to the shuttering of museums throughout the globe, many cultural institutions promoted their online visits in order to connect people to their collections.

To my delight, I could visit not just MoMA but the Met, the Philadelphia Jewish Museum, and even virtually return to the British Museum and the Tate after a trip there in London last summer- it’s not a surprise that I stayed up till 3:00 am digitally sauntering past the Rosetta Stone and down the stairs in the Tate towards Modernist classics.

It seems, then, like a glorious idea: if museums can enrich our understanding of people no matter our nationalities, surely Google’s service, accessible at no charge to almost all smartphone users, is a boon to all people.

Is it, however? The cultural changes that have swept America and the globe since the police killing of George Floyd rocked and continue to rock seemingly all institutions, and galleries and museums are not exempt.

Activists have issued demands that include the usual steps to address overwhelmingly white boards of directors and to cut ties to police and industries such as tear gas manufacturers. A lot of this isn’t new- it builds on efforts by activists stretching in many cases back to Occupy Wall Street.

Going beyond this, though, some groups have called into question the idea of the museum itself, as a colonial enterprise inherently rooted on the looting of artifacts belonging to people that saw their heritage seized at gunpoint during the imperialist era and sent to institutions such as the Met, and most notoriously, the British Museum.

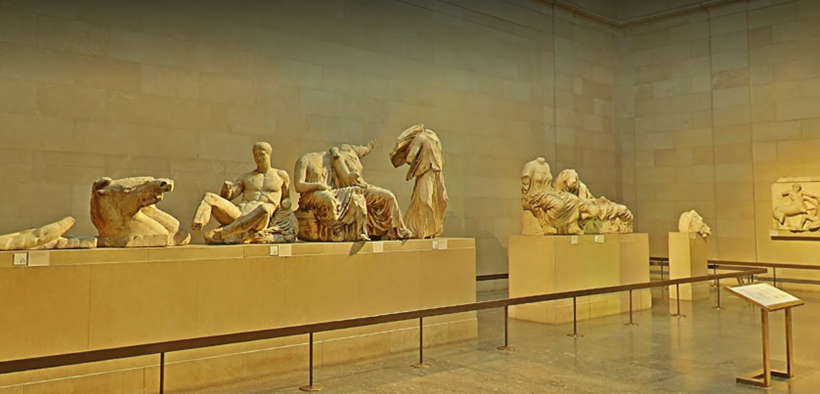

Studying in Britain in the summer of 2019 as part of Klein Go’s London Summer Experience, our class discussed the Elgin Marbles controversy (you can read a summary here) and the British Museum as a “crime scene.”

The question becomes this- as a multinational conglomerate that already has enormous power over culture and media (Google Books has the aim of archiving every known piece of literature, and billions of people receive their news via the search engine), is Google appropriating the cultural heritage of colonized people? If controversies surrounding the relocation of artifacts have been a sore spot in national disputes between countries such as Greece and the UK, a museum that gives Google permission to archive their collection is obviously not giving any say, or royalties, to the countries and tribes that themselves are trying to recover their heritage.

One answer to all of this is to abolish museums, and declare the entire concept racist and irredeemable. That has been the approach of groups such as Decolonize this Place and Representation Matters, two Black Lives Matter-affiliated groups that have recently gained attention, including a reference in the New York Times’s Sunday style magazine.

It may not end up mattering. As arts and culture budgets reel under spending cuts at the time of a health crisis as international as the British Museum’s holdings, some might view spending on institutions deemed racist and a “Jim Crow” legacy among activists and as a luxury among conservative deficit hawks to be a needless expense.

However, perhaps the pandemic can also provide us a different insight. If culture is online, let us say, out of the control of Google but available to all via a creative commons or an international organization such as UNESCO, perhaps the idea of “ownership” can be seen as obsolete.

As I’ve experienced them, is untrue that museums and galleries are backwards-looking institutions, despite drawing on an (often tragic and problematic) history. They can aid in building connections towards a more interconnected world in our time and beyond.

Allowing our interactions to historical and artistic treasures to be dominated by the past or by the injustices of the present is only going to increase our sense of afraidness towards the idea that things can ever change. And that, amidst our current international grief, is a cancellation of something much more valuable than one student’s winter MoMA trip.